More than 50,000 people competed in The Great North Run in Newcastle, England on September 18, 2005. Approximately 30,000 finished the race and four people died trying to finish it. Mark and his father Keith were not among those who died. They finished the half marathon, and they finished it strong. Another participant in The Great North Run was Thomas from York, England. His time was “under an hour and thirty.” This was a good showing in terms of half marathon times, and for Tom it partly made up for his disastrous run during the Easingwold Cross-Country Championship trials in Yorkshire when a course officiator sent him in the wrong direction.

“I’ve done fuck-all this morning, Dave,” Tom told me two days before the April 1st Prague Half Marathon. It was a familiar phrase from him at the time. “I can’t be arsed” and “I can’t be bothered” were two others. They meant the same thing: I haven’t done enough to get me to where I need to be for this race.

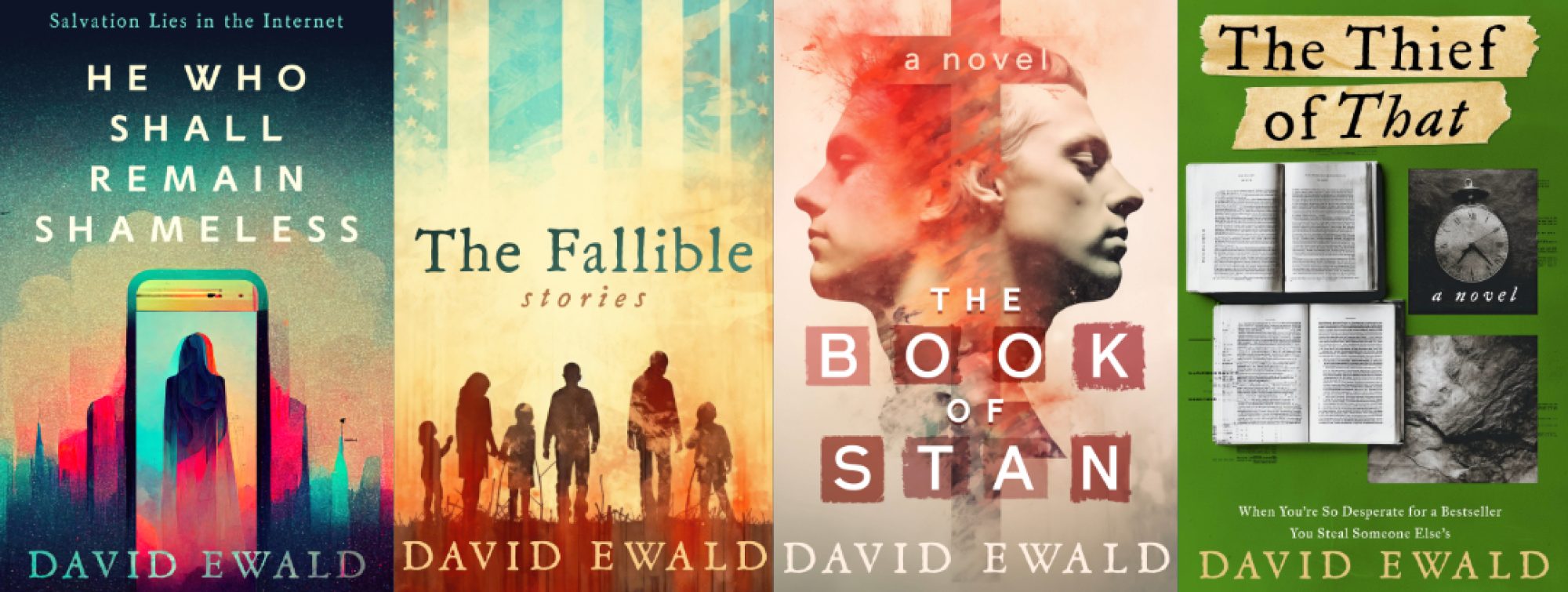

With Tom I shared an aging but warm communist-era flat located in Lesná Certova Rokle (literal translation: “Evil Canyon in the Woods”), a suburb north of Brno, the second-largest city in the Czech Republic. I also shared the flat with Mark. The three of us were flatmates and fellow EFL (English as a Foreign Language) teachers working for ILC International House language school.

In the lead-up to the race I asked what possesses people to pound the pavement — or, in the case of the Prague Half Marathon, cobblestones — for thirteen miles and then agree to do it again in a little over a month’s time?

“You gotta get the marathon out of your system,” Keith told me two days after the Prague run. At fifty-one years of age and with a finishing time of an hour and thirty-four minutes, Keith just might have gotten the marathon out of his system at last. He’d run three previous marathons, all of them halves, and wanted to run in more but his wife was worried he’d get too thin and never adequately recover.

For Erik, an American standing six feet three inches tall, it was both a means to lose a little weight and to kindle camaraderie amongst the ILC staff. In mid-January, in the midst of what authorities and our students were calling the worst winter to hit the Czech Republic in forty years, Erik emailed a document to many of us teachers. The document was a training schedule which I promptly titled “Erik’s Schedule o’ Pain.” It wasn’t just that we would be running every weekend with a gradual increase of two or three kilometers (about a mile) every week until we at last reached the twenty-one kilometer pinnacle. It was also that we would be running in the snow, across hidden ice patches, in the deep chill, and later the mud and the mire. We would be running in January. We would be running in February. We would be running in March still with no sign of birds chirping, rushing rivers whisking away winter’s runoff, the voices of Czech children again playing in the park close to our Evil Canyon in the Woods flat.

Despite the title I gave Erik’s plan, I committed. At least in the beginning, I committed. I went on the first run (three kilometers around Luzanky Park), I went on the second (again around Luzanky, only this time five kilometers). I even went on the third run, a seven kilometer haul around Lesná. It was during this seven-k run that I realized something: I intensely disliked running. I had never liked it, and I wasn’t about to do an about-face now. My life did not depend on it, as I wasn’t running from an advancing army, conquering aliens from outer space, or Godzilla. I didn’t have to commit to the training, and if I didn’t have to commit to the training I also didn’t have commit to the race. I was 27 and could make my own decisions.

On the last weekend in January, a Saturday I think, those who had participated in the seven-k Lesná run gathered for lunch in the nearby Salve Club restaurant and there I looked across the table at Erik, who could be very hard to say no to, and told him just that: no, no and no again. I was sorry but I wouldn’t be running in the marathon. I was pulling out.

Erik looked at me with his soft saturnine eyes. He took a moment before answering. When he did it was with words I hadn’t expected. “That’s okay,” he said. “At least you came out.”

This was true, and it helped me to save some face. Other recruits either said they would go on the runs and then didn’t show up at all or they knew right away how the training would end for them and let Erik know from the start that they wouldn’t be participating. For me it took a total of three runs as evidence that this kind of thing was not in my realm of possibility. In truth, I sold myself short. I blamed my bad knee that I’d had surgery on when I was twenty. I blamed the weather. I blamed my pair of three-year-old threadbare basketball sneakers. I deflected, and I got testy. When Ali (Alison), a young Brit from just south of Oxford, found out I had dropped the training and therefore the race itself, she said to me, “But you’re fit.” “I am fit,” I responded, a bit petulantly. “I don’t need to prove it. And I just don’t think I’d like running a marathon.”

I believed I was fit, anyway, and I continued to blame and deflect. I blamed the distance. I was fine with short runs, I told myself. If only the race were shorter, like a sprint. With a 100-meter dash I knew the end was in sight; I could, after all, see that end. While running around Lesná that last Saturday in January I couldn’t see an end — not physically, not mentally and certainly not emotionally. And here, two decades later, is the truth, involving not the physical but rather the mental and the emotional, who I really am: I did not trust myself then. I did not trust my body. Above all, I feared failure. I feared courting embarrassment in front of so many of my fellow colleagues, whom I wanted to make my friends, and one of whom I was, in all honesty, genuinely falling in love with. I feared once I started the Prague Half Marathon I would not be able to finish it, I would have to, at best, walk it starting well before the midway point, and all the ILC teachers would know, and my embarrassment would be too great to overcome. I would never live their disappointment in me down.

To paraphrase the writer J.R. Ackerley: The fear of failure caused me to fail.

My mind went to some outlandish, scary places. Perhaps I wouldn’t make it to the finish line. Perhaps the marathon officials would sweep me off the cobblestones at the end of my three-hour time limit — and I wouldn’t even be close to the finish line. Perhaps I would just die. I thought of those four unfortunate people, all in their thirties, who’d wandered off the path of The Great North Run on September 18, 2005, lain down somewhere and perished. I thought of them and I thought of my self-induced pressure, my single-minded commitment, the fact that once I started I would have to force myself to finish, possibly at the expense of my life. So I psyched myself out early on. What can I say? I couldn’t be bothered.

Saturday, April 1, 2006 dawned cold, cloudy and damp over Prague. The day before we — that is, the ILC running team and its associates — had taken buses or trains to the Golden City and checked into our hostels. We all met up for dinner at Pizza Colosseum in the main square that night and I and my fellow drinking team did what drinking teams do best: we got our drink on. At least, that had been the plan anyway. The truth is that first night in Prague Vendy (Vendula) had mineral water and Beth and I had only one beer apiece. Only Aram and Justin, Erik’s friends who’d flown in from San Francisco for the express purpose, in the big guy’s words, “of womanizing,” fully represented the ILC drinking team by downing three or possibly four pints each. The sight of so many of my colleagues on their best behavior the night before their big race sobered me up and kept me from imbibing in my usual more-than-one-drink-a-dinner fix. I did manage to sneak in a couple more later that night when Aram and I went looking for bars near our hostel.

The next morning, the morning of the big run, Beth and I followed part of the ILC running team from the hostel to the meeting point on Charles Bridge. Once there the drinking team found it could go no farther. Charles Bridge was packed with participants, many of whom were squeezed to the very edge of the walls overlooking the Vltava River, which had recently flooded due to severe rains. A total of 3,500 would run that day, and Beth and I, who had hoped to get some grand picture of all ten ILC runners on the Charles Bridge in the late morning spotty and sporadic sun just as they took off, had to settle for a mediocre shot of the backs of Erik, Tom, Mark, Keith and Ali as they climbed the steps leading to their starting point. At a little after noon on the first of April, the great half run began with a bang. I had by this time lost sight of every one of the ILC marathoners. I only saw a mass of people pressed in together and streaming steadily across the bridge, from the north, the castle side, to the south where most of the hardest-fought moments of the run would take place. I looked up and saw clouds coagulating and darkening overhead. It would be a much different day than that of The Great North Run in Newcastle.

Beth and I spent some time on Charles Bridge taking our own shameless pictures. For a drinking team we weren’t doing much drinking. Before the run we’d planned join Vendy and really show the running team what our livers were made of: steel. But once the marathon was underway and we actually had time away from the running team, we had the darnedest time trying to come together as a cohesive unit. I texted Vendy to tell her where we were while Beth waited by the statue of a famous Prague prince or king who was thrown into the Vltava, wearing his armor, and thus martyred for some cause I can’t remember now. Vendy texted back saying she was in the Old Town Square and would be joining us shortly. That “shortly” turned into “a while.” The drinking team simply couldn’t get it together.

Meanwhile, on the running team front the marathon was going well for some and reasonably well for most. Tom and Mark of course took off like gazelles chased by cheetahs and Mark’s father Keith wasn’t far behind. At a considerable distance behind them were Erik, Ali, Bara, Susan and Marketa. After the marathon Erik would describe to me the path and the facilities available to all runners, how elderly Czech women stood on either side of the path waving and offering cups of water. How there was enough water but not nearly enough places to take a bathroom break. How when you looked up from the cobblestones beating your feet you would be lucky to see a marker on a billboard or some other indicator that told you how many kilometers you had left to run. How the markers were all off according to Erik, who said he saw a five-k marker followed by an eight-k when he knew he hadn’t run nearly that far, or he saw an eight-k marker followed by a nine-k when he knew he’d run farther than that. So the most convenient methods of measuring your pace were all screwy and towards the end of the run, during the last three-k or so, Erik plugged in his portable MP3 player and kept rolling since by that time Ali had broken from him and left him behind.

And so it was no surprise that at an hour and twenty-seven minutes into the marathon Tom pulled around the corner, under the archway of the Charles Bridge, and pushed for the finish line, his vest (what we in the States would call a tank top) soaked and his cheeks puffing like those of a fish out of water. He didn’t look good; he looked glorious. Beth and I were watching from the right side of the fenced path and when I saw Tom keeping pace with a couple of other runners I shouted to Beth, “Tom! Tom!” We had expected either Mark or Tom to be first, and Tom took the prize. Vendy joined us as did Aram and Justin who were the only two members of the drinking team to actually drink during the marathon, having found a quiet little pub just south of Charles Bridge. As one cohesive unit, a force of togetherness at last, we cheered on the remaining ILC runners. I managed to get off a picture of Tom, of Mark and even one of Mark’s father who I recognized only from seeing a picture in Mark’s room once. But I missed Mat, I missed Brian who whizzed by me, a fact that Aram pointed out albeit too late, and I recovered in time to catch Marketa, the fastest of the ILC women. I had my camera at the ready for the remaining four. I was expecting to see Erik next, pushing his big frame toward the finish, but from around the corner came Ali instead, running as if she were possessed.

As is my luck from time to time, I had my camera off and shuttered as Ali ran toward me. I had a full-on view of her and along with Tom’s and Mark’s it would have been the best of the pictures taken of ILC runners. But I bunged it up. By the time the camera was on, focused and ready shoot, Ali had blown by me and was nearly to the finish. The rain had started coming down semi-strong and I was carrying her things, jumper, purse etc. so I took off to find her. Once I’d located her and Marketa walking together I handed Ali her belongings and tried to fight my way back to my original position as observer and amateur photographer. But by then it was too late to take pictures of the rest. In the interim between delivering Ali her things and getting back to my spectator spot I’d missed Bara. I didn’t know how far Erik and Susan had to go, so I left. I left them to the rain and the cobblestones and the professional photo-finish at the end of the line.

After the marathon, as people were getting their free massages or paying to have their medals engraved with their names and finish-times, Erik started mentioning Vienna. The run, another half marathon, was on the 7th of May. Who was in, who was out?

Responses varied from the definite commitment (Mat) to the tepid maybe (Susan) to the outright no (Ali). Again Erik pressed me for recruitment; I told him I’d think about it. I had over a month to prepare, the weather throughout the Czech Republic was turning pleasant with the approach of spring, and Vienna was a flat city meaning the terrain would not be at all difficult to tackle. And besides, hadn’t I said to Ali just after she finished “I could’ve done it. I should’ve ran”? After hearing those words Ali had looked at me funny. After all, I’d been so adamant about not running that to express regret now must have seemed to her quite odd. But I couldn’t help it. That regret had been real.

It had started as I was watching not the first several runners cross the finish line but rather the middle of the 3,500-strong pack. At least in appearance many of these mid-finishers were not the fittest and their ages varied to such an extent that I was left both astounded and a bit envious. I saw men in what must’ve been their sixties sprinting side-by-side to the finish line with people less than half their age. I saw short round iPod-bound women wearing thick spectacles and pushing themselves far beyond my threshold. I saw a man closer to my age dragged across the finish line by his fellow runners. Dragged, yes, but he finished. And where was I? What was I? I was a 27 year old seemingly healthy male who instead of participating in the run with his colleagues, his friends, had opted instead to hold their belongings and take pictures of them as they approached the finish line. Was I a coward? Was I lazy?

I know the answers now; I suspected the answers then. I could make up for my fear and self-loathing by doing the Vienna Half Marathon in May. Despite this reasoning, I was leaning toward no as an answer. Committing to Vienna would mean giving up beautiful-weather weekends that would otherwise be spent traveling to remote national parks or cities within the Czech Republic. It would also mean having to buy actual running shoes and train in them. It would mean a lot. It would mean more than I was willing to give. And so I said no. I’d mentioned the possibility of Vienna to Vendy who was seriously leaning towards a yes, but later that night, as we all gathered for well-earned drinks in Lucerna, an eighties and nineties dance club in the city, I retracted my previous interest and hit Erik with a definite no. Not this time, not ever. The best I would do, I told the big guy, was the Bay to Breakers, held every May in San Francisco.

And as we danced — or, in some of the ILC running team’s case, staggered and swayed — to Banarama’s “Venus,” Lou Bega’s “Mambo Number Five” and, of course, “The Macarena,” I felt the pressure off, though the regret remained, my future shrouded in webs of worry. I was dancing with my friends, but I was dancing alone.